back to abstracts – back to annual meeting

Alessandro Cavalli

|

Once educating meant transmitting the heritage of knowledge accumulated over the centuries to the new generations, so that in their future life they could face the problems that previous generations had already solved, without having to start from the beginning each time.

Since human societies have entered a process of accelerating change, which does not seem to be stopping at the moment, educating young people also means preparing them to face problems in a world we do not yet know, we only know that it will be different from ours and from that of past generations. For example, what does it mean to educate to live in a society in demographic decline when humanity as a whole experiences a demographic explosion? What does it mean to prepare to face the possible gradual disappearance of manual labor, at least in the forms known to us?

Change inevitably generates resistance and enthusiasm.

Change inevitably generates resistance and enthusiasm.

The task of education is not to strengthen resistance and enthusiasm, but to train young people to live the change consciously.

We talk about globalization, we do not know which directions it will take, but we know it has and will have important implications for every local community, for the environment each school is a part of, for the daily lives of all its members.

Jeffrey Holte

|

Liger Leadership Academy (LLA) is boldly changing the paradigm of teaching and learning in one small developing country.

In 2019, most schools in the world continue to operate in similarly traditional ways, and the learning that occurs is not fully aligned to meet the needs of today’s students. We must completely rethink how they will gain knowledge and expand skills to increase forthcoming educational and economic opportunities. Through engaging authentic experiences, future-skills development, and youth empowerment, LLA students are being prepared to thrive and succeed in an increasingly complicated world.

The goal of LLA is to develop ethical and innovative leaders for Cambodia. Leadership is an advanced and complex competency and demands opportunities for students to engage in the people, places, challenges, and possibilities in their own country. By contextualizing learning and empowering students to solve real-world problems, LLA seeks to develop a societal understanding and pride that goes well beyond nationalism. In addition to content knowledge and traditional academic proficiencies, students build an individualized toolkit of future-skills that includes collaboration, communication, dot-connecting, networking and self-awareness to name a few.

The goal of LLA is to develop ethical and innovative leaders for Cambodia. Leadership is an advanced and complex competency and demands opportunities for students to engage in the people, places, challenges, and possibilities in their own country. By contextualizing learning and empowering students to solve real-world problems, LLA seeks to develop a societal understanding and pride that goes well beyond nationalism. In addition to content knowledge and traditional academic proficiencies, students build an individualized toolkit of future-skills that includes collaboration, communication, dot-connecting, networking and self-awareness to name a few.

Education is experiencing perhaps its most critical moment in history. The speed at which our world is changing is exponential, and the time is now for schools to adapt and keep pace by inventing and implementing new standards of practice. Whether the change is a large-scale initiative like LLA or incremental changes to an existing program, we must be courageous leaders to ensure a bright future for our youth.

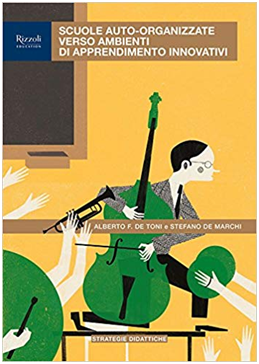

Alberto De Toni

|

Self-organizing school represent a bright prospect on the horizon of education. In favour of this thesis, the results of a research carried out in 14 Italian schools will be presented; they will highlight positive correlations between school self-organization and innovative learning environments. In other words, the more schools are self-organized the more learning environments are innovative.

The outcomes of this empirical work first show the empowerment of teachers, scientific associations, communities of practice, and secondly of schools, their leaders, networks and governing bodies. The top – the Department of Education, Regional and Local School Authorties, Support Agencies (Invalsi, Indire) etc- have the remaining key tasks of defining policies, allocating resources, implementing accompanying measures, setting up networks, evaluating outcomes, etc.

Resistances to self-organization come from both the top and bottom of the school pyramid.

The resistance from the top derives from the fact that a greater school autonomy is seen as a reduction in the capability of the Department of Education to keep everything under control. The essential conceptual step to overcome resistance from the top is to understand that self-organization does not imply loss of power. Power is like knowledge: it can be duplicated. The conceptualization of power as a non-zero sum entity is the critical step to understand the nature of empowerment and management of many-minds systems. Empowerment is neither an abdication of power nor a sharing of power. It is a duplication of power.

But the resistances also come from the bottom. Hierarchy, illusion of order, control and predictability are much safer and more reassuring than self-organization. The resistance from the bottom will be overcome only when all school actors have a common inspiration, dream, passion in the discovery, research, and construction of something meaningful to their own story, to their own project of life and to a more equitable, inclusive and cohesive society.

But the resistances also come from the bottom. Hierarchy, illusion of order, control and predictability are much safer and more reassuring than self-organization. The resistance from the bottom will be overcome only when all school actors have a common inspiration, dream, passion in the discovery, research, and construction of something meaningful to their own story, to their own project of life and to a more equitable, inclusive and cohesive society.

Self-organization needs energy. Energy is necessary for complex adaptive systems – schools and classes – to self-organize. This flow of energy is guaranteed by the intrapreneurship of the teachers (in the classroom) and of the school leaders (in the school). The school will change if its actors push it from the bottom.

In a school that fosters self-organization, school leaders and teachers move from a traditional role of “planning and control” of school and learning, to a new one of “creation and oversight” of the context of school and learning. A context where the true motivation is self-motivation as a result of a shared vision, sustained by the example of its leader who provides the energy of change.

What is needed is a distributed, inter-connected, self-motivated and self-activated intelligence. No solution will come from the centralized Department of Education, which is necessary, but not sufficient. The future is in the periphery, inside the self-organizing schools, capable of promoting fruitful interconnected networks of students, teachers, technicians, leaders and schools: self-organization is the most fascinating future for our schools.

Marius C. Felderhof

|

If one seeks to understand the world globally, it soon becomes apparent that different religious traditions have exercised, and continue to exercise, a profound influence on diverse cultures in other countries and, increasingly, within Europe too, mainly due to immigration. It may be disconcerting to a secularised Europe to discover that religions and religious institutions still wield so much influence, for good or ill, over the lives of so many people (estimated at 85% of the world population).

In Britain the initial educational response to prepare young people for this religiously plural world has been to offer the secular study of ‘religions and belief’ in place of the legally required “confessional” religious education. It is argued that this initial educational response is inadequate and that educationally there is a more constructive way forward that is (a) more realistic, (b) more accurate as to what religions are about and (c) more beneficial to pupils.

The paper begins by acknowledging the important constraints on curriculum planning, namely, those derived from human finitude. This demands a more serious realism on the part of the curriculum planner as to what can and should be done in the classroom than is often the case.

The paper begins by acknowledging the important constraints on curriculum planning, namely, those derived from human finitude. This demands a more serious realism on the part of the curriculum planner as to what can and should be done in the classroom than is often the case.

But then the paper goes on to consider the proper focus of religious education. This is not so much about the various religions themselves as about the fundamental interest of religious traditions. Unlike Religious Studies, which is frequently socially divisive in its outcome, the fundamental interest of religions in “living well” draws religious traditions and the secularist together, complementing and reinforcing insights that each may bring. This fundamental interest is shown to have moral and spiritual dimensions as well as global import. It also establishes that a key focus of Religious Education is the character development of pupils, encouraging an openness to others and nurturing a global concern. This character development has cognitive (Intellectual), affective (Feeling) and conative (Will) dimensions. An interesting question is whether educational interventions within RE do actually have an impact on character development. A small scale pilot study undertaken in schools in Birmingham and Liverpool has yielded encouraging results on the part of both pupils and teachers.

Raini Sipilä

|

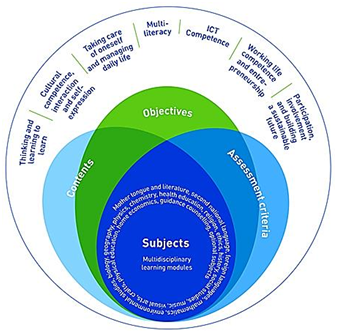

The new National Curriculum took place in Finnish Basic education on 2016. It was first introduced for grades 1 – 6 (primary school) and later on for grades 7 – 9 (secondary school). Education providers have drawn up their own local curricula based on the National Curriculum.

The reform in Finland is about rethinking learning and learning environments. It is about giving active roles to students, giving respect for students’ own questions, ideas and experiences. It is about teachers’ flexible ways of being a teacher. There have been many debates and reactions to the reform, both for and against it.

After the reform newspapers all over the world have had headlines like: “Finland is to abandon subject teaching” “Could subject soon be a thing of the past in Finland”. Phenomenon based learning in these newspapers was seen a revolutionary way of both thinking and teaching. But the word Phenomenon Based learning itself is not even mentioned in Finland’s National Core Curriculum.

After the reform newspapers all over the world have had headlines like: “Finland is to abandon subject teaching” “Could subject soon be a thing of the past in Finland”. Phenomenon based learning in these newspapers was seen a revolutionary way of both thinking and teaching. But the word Phenomenon Based learning itself is not even mentioned in Finland’s National Core Curriculum.

Surprisingly the Finland’s National curriculum is based on subjects. But the things which are new, is the idea of transversal competences, multidisciplinary models and coding. Transversal competences are part of every subject, they are:

- thinking and learning to learn;

- cultural competence, interaction and self-expression;

- taking care of oneself and managing daily life;

- multiliteracy;

- ICT competence;

- working life competence and entrepreneurship;

- participation and involvement and building a sustainable future).

Students are evaluated in various ways, there is lots of diversity in assessment: self-evaluation, peer evaluation, oral /written feedback and school year report. Assessment is based on target sets in every subject; the aim of evaluation is to support students learning.